Inside Sting's First Rock Album in Decades - How Prince's death, climate change inspired "impulsive" new LP...

July 25, 2016

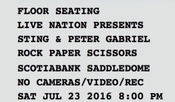

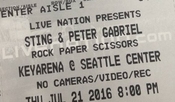

It's a perfect Saturday morning, but Sting, unshaven and scruffy, is lying on a couch in a darkened New York studio, taking a nap before starting work for the day. He's still recovering from playing New York's Jones Beach Theater last night, the third date of his co-headlining summer tour with Peter Gabriel. "That was a workout," he says. "I've been up since 5:30. I'm the son of a milkman." Sting is working overtime to finish 57th & 9th (named after the intersection he crosses to get to the studio every day), which has him returning to the guitar-driven rock music he hasn't made in decades. "It's not a lute album," he says with a smile, a reference to 2006's Songs From the Labyrinth. "It's rockier than anything I've done in a while. This record is a sort of omnibus of everything that I do, but the flagship seems to be this energetic thing. I'm very happy to put up the mast and see how it goes."

Ship analogies may be on his mind because he spent the past several years writing, and ultimately acting in The Last Ship, a 2014 musical based on his childhood in postwar England. The project followed a productive, freewheeling decade of work that included an LP of Christmas carols, the orchestral Symphonicities and a marathon reunion tour with the Police in 2007 and 2008 – which he stresses did not influence the sound of his new LP. "That reunion was an exercise in nostalgia, clear and simple," he says. "A very successful exercise in nostalgia, but there was no attempt to take that somewhere else." The Last Ship made it to Broadway, but closed after three months. "I found it very gratifying to get it that far," he says. "It was the most satisfying five years of my life." After it closed, Sting found himself with some rare downtime. "I'd walk through the park, and there wasn't much difference between me and somebody who doesn't have a job. Well, I've got a home to go to. But I start to get anxious."

So he took the advice of his new manager, Martin Kierszenbaum – who worked as Sting's A&R man before getting hired full-time earlier this year – and booked studio time with a small group of musicians. They included his touring drummer Vinnie Colaiuta and guitarist Dominic Miller, and Jerry Fuentes and Diego Navaira of the Last Bandoleros, a San Antonio Tex-Mex group that Kierszenbaum also manages. Sting arrived daily without any material and wrote on the spot with the musicians in the studio. "It raises the tension, because everything costs money," he says.

"Most of it was done in an impulsive way," says Kierszenbaum, who produced the LP. "One or two takes. I don't think he's rocked like this since Synchronicity."

Much of the album, Sting says, is "about emigrating." "Inshallah" tells the story of refugees traveling to Europe. "One Fine Day" takes aim at climate-change skeptics. "The biggest engine for migration will be climate," he says. "Millions of people will be looking for somewhere safe. I'm still in a bit of a depression about Britain exiting the EU for no good reason. At least the EU has a program to tackle climate change." "Mortality does sort of rear its head, particularly at my age."

One highlight is "50,000," a gloomy ballad he wrote the week of Prince's death. Sting describes the process of reading the obituary of one of his rock & roll peers in the song, recalling stadium glory days together before existential fear settles in. "Mortality does sort of rear its head, particularly at my age – I'm 64," he says. "It's really a comment on how shocked we all are when one of our cultural icons dies: Prince, David [Bowie], Glenn Frey, Lemmy. They are our gods, in a way. So when they die, we have to question our own immortality. Even I, as a rock star, have to question my own. And the sort of bittersweet realization that hubris doesn't mean anything in the end."

Sting had his last commercial smash when he was 48, with 1999's Brand New Day, which won two Grammys and went multiplatinum. This time, he's keeping his expectations in check. "The record industry is in a state of chaos and flux," he says. "I have no idea what expectations are. It's not like the old days. Rock & roll is a traditional form now. It's not socially cohesive like it used to be." But that's why he sees it as the right moment to return to the genre. "For me, the most important element in all music is surprise. I'll keep throwing curveballs. It's my journey; people are welcome to share it with me." He laughs. "I really do what the fuck I want."

(c) Rolling Stone By Patrick Doyle